Adventure: Exploring New Places

This is the fifth in a series of blogs posted in early 2025.

When I was at primary school in the fifties, my sister became best friends with our doctor’s daughter Jenny. She visited our home a lot, and we went to hers, a large property with a tennis court and lots of room to run around. We would read Enid Blyton stories, and Jenny would tell us about all the wonderful places she had visited while living in England for a year. Her adventures prompted a deep longing in me to go to Europe, to see Buckingham Palace and the Tower of London, to walk on cobbled streets and to take a train from Paddington Station. Ten years later, many of my fellow university students visited the UK after graduation; it was called the Big OE (Overseas Experience) and included working in pubs or as a nanny to make enough to go on a four week bus tour to Europe before leaving. On the return to NZ to teach or nurse (for girls) or build bridges or keep accounts (for guys) they would have grown up a lot and be more worldly-wise than those who stayed in New Zealand. The stay-behinders included my husband and I. We didn’t travel, as he was a young doctor and needed to work for three years in a hospital to become fully qualified. I didn’t mind, there weren’t many jobs for women pastors and we wanted a family anyway. But I never lost that longing to travel and to visit foreign places where people spoke French or Italian or even just English with a plum in the mouth.

Later when the kids were aged 6, 8, 10 and 12, we exchanged homes with a Bristol GP for 8 months. We got to take the family to lots of those foreign climes, with their unfamiliar languages and memorable architecture. The allure of a new place is something we’ve continued to enjoy, now that the children have grown and we can afford for just the two of us to fly off into the sunset.

Later when the kids were aged 6, 8, 10 and 12, we exchanged homes with a Bristol GP for 8 months. We got to take the family to lots of those foreign climes, with their unfamiliar languages and memorable architecture. The allure of a new place is something we’ve continued to enjoy, now that the children have grown and we can afford for just the two of us to fly off into the sunset.

Now the Lord said to Abram, ‘Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you. I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you and make your name great, so that you will be a blessing. I will bless those who bless you, and the one who curses you I will curse, and in you all the families of the earth shall be blessed.’ Genesis 12: 1 – 3

I don’t imagine Abram had visions of an Eiffel Tower or a London Bridge that he longed to see. The new place that God called him to was clouded in uncertainty; He went out, not knowing where he was going says the writer to the Hebrews in 11:8. This demanded a huge trust of both Abram and Sarah. Yet agreeing to the journey would bring great blessing to many, and provide the setting for the foundation of the Jewish faith and, in time, the historic Christian story.

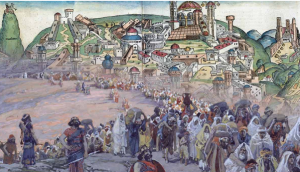

Journeys and travel are themes which return regularly throughout the Bible. Many individuals in the story of the people of God are called to move out of a place which is comfortable and familiar and go to a new place. where they will experience God in new and transformational ways. Think for example of Moses, Ruth, Babylon and Bethlehem. The stories of these Biblical Sojourners is perhaps best seen in the Babylonian Exile of the 6th century BCE. We hear about this in 2 Kings, Isaiah, Jeremiah and Ezra as well as the whole book of Daniel. The Hebrew Bible says Israel had forgotten what it meant to truly live as God’s people. After a slow decline and many warnings from prophets, God ordained a time of exile, where most of the Jews were carried off to a foreign land.

There in Babylon they had to learn a new language, eat different food and follow mysterious customs. The comforts of their normal life were gone, their family routines had been disrupted, and the familiar sights and sounds of their lives in Judah were far far away. But they remembered and put into practice what the prophet Jeremiah had said about this:

There in Babylon they had to learn a new language, eat different food and follow mysterious customs. The comforts of their normal life were gone, their family routines had been disrupted, and the familiar sights and sounds of their lives in Judah were far far away. But they remembered and put into practice what the prophet Jeremiah had said about this:

This is what the LORD of Heaven’s Armies, the God of Israel, says to all the captives he has exiled to Babylon from Jerusalem: “Build homes, and plan to stay. Plant gardens, and eat the food they produce. Marry and have children. Then find spouses for them so that you may have many grandchildren. Multiply! Do not dwindle away! And work for the peace and prosperity of the city where I sent you into exile. Pray to the LORD for it, for its welfare will determine your welfare.” Jeremiah 29: 4 – 7

The book of Daniel has passed down to us some well-known stories – the moving finger, the lions’ den, the fiery furnace. Daniel and his companions had died before Ezra and Nehemiah came on the scene and gained royal permission to return to the homeland. But 70 years on, those who did return took with them new ways of practising their religion. In Babylon with No Land, No Jewish King, and No Temple, their faith had survived as a commitment to holiness. They learned to pray without the assistance of priests or sacrifices. They saw God was still present, in nature and art and family and human kindness. Many no longer spoke traditional Hebrew, as the Aramaic of Babylon had become their common tongue. There was no official holy day or holy food, so they had to take individual responsibility for living out their relationship with God. Without the powerful Temple cult to structure gathered worship, village synagogues began to arise, teaching the faith in groups of twelve families. And because they needed to know the Scriptures far away from the priests who controlled the discourse in Judah, the role of scribes took on more importance. One Jewish writer says the exiled Judeans developed an “unprecedented creative energy” that over time resulted in existing scriptures being edited and new psalms and histories being composed. Such positive byproducts of exile remained in place even after the Temple was rebuilt, and would sustain them through other periods of oppression by foreign nations. By the time Jesus came, these changes were bedded in, and like the Roman roads and the Greek language, enabled the good news of Jesus and his everlasting kingdom to take root and flourish around the world.

The experience of Exile has a universality that has seen it applied to many contemporary events. It is how Palestinian Christians see their plight; for them, their exile is a “space where you are constantly aware you are not at home.” And I’ve seen others use the paradigm; a Polish person living in postwar Germany, a Cuban exiled in the USA, a Kiwi missionary living in Romania. People around the world wrote of our periods of Covid lockdown being a kind of exile. Yes, we were mostly in our own homes but experienced that sense of dislocation, discomfort, dis-ease, where we had to get used to a new normal of mask-wearing, social distancing and Zoom church. Some of these consequences remain in our New Normal.

How can we take encouragement and hope from the ways Daniel and his contemporaries engaged with their foreign context and found new paths to holiness and community? Could feeling dislocated also be a positive experience for the People of God today? Change itself keeps accelerating. Moral ambiguity, technological advances, and unpredictable weather undermine our certainty. In New Zealand today, churches are accorded little respect, and faith practices like prayer and Bible reading are declining within congregations, as much as around them. Globally, faith communities are plagued by consumerism, scandal, financial recklessness, and colonial attitudes that undermine our voices for justice.

This has led some writers like NT Wright and Walter Brueggeman to suggest that faith communities are in a new place of exile, a cultural reality that isn’t so much a physical dislocation but a spiritual condition, where we are at odds with the prevailing culture. But if we are exiles, then perhaps we too are ripe for a reimagined Hope.

Whether you go to new places as visitors, or settlers, there is much to be learned from engaging with strangers and thoughtfully adopting new practices as we learn how to seek the peace and prosperity of our own cities.

Often when I’m preparing people for believer’s baptism, I get them to share a timeline of their spiritual journey, and what has brought them to this commitment. Its interesting how the challenge of physically moving in to a new space – home, country, job or marriage – is often cited as the trigger for something new in the experience of God. Certainly when we shifted to Bristol, I underwent a kid of identity crisis. I had been the doctor’s wife in a town of 4000 people back in NZ. In Bristol no one knew who I was, what I had studied in depth or where I had worked. The fact that we were traveling most weekends meant hospitality or nannying weren’t options. And GPs in Britain work long days. The local Methodist minister visited me at home several times, but was shocked when I eventually apprised him of the fact that I was ordained. When he asked why I didn’t just tell him, I was embarrassed to admit that hostility I had faced at home meant I was terrified he too didn’t believe in women ministers. ( That was not the case, and I did get to preach for them – but it was our last Sunday!)

Often when I’m preparing people for believer’s baptism, I get them to share a timeline of their spiritual journey, and what has brought them to this commitment. Its interesting how the challenge of physically moving in to a new space – home, country, job or marriage – is often cited as the trigger for something new in the experience of God. Certainly when we shifted to Bristol, I underwent a kid of identity crisis. I had been the doctor’s wife in a town of 4000 people back in NZ. In Bristol no one knew who I was, what I had studied in depth or where I had worked. The fact that we were traveling most weekends meant hospitality or nannying weren’t options. And GPs in Britain work long days. The local Methodist minister visited me at home several times, but was shocked when I eventually apprised him of the fact that I was ordained. When he asked why I didn’t just tell him, I was embarrassed to admit that hostility I had faced at home meant I was terrified he too didn’t believe in women ministers. ( That was not the case, and I did get to preach for them – but it was our last Sunday!)

Relocating to a new place made me more conscious of my need for God’s guidance, wisdom, and provision. The uncertainty that comes with such a move compels us to rely more deeply on our faith and its spiritual practices. In my experience, it can be a time of growth.

Reflecting on how our relationship with God has evolved can be a valuable exercise in understanding how it might continue to develop in the future. In fact, we often see patterns reprising time and again, as God continues to embed his values and character in our journey.

Try mapping a timeline of your journey of faith, identifying the people, places and experiences that have shaped it over time. And invite God to use those ups and downs to shape your own gifts and call, even in times of uncertainty:

Trust in the Lord with all your heart; do not depend on your own understanding.

Seek his will in all you do, and he will show you which path to take.

Proverbs 3: 5,6